Revenge Might Not Solve Everything, But It’s Fun – A Review Of The Dishonored RPG

Alex and friends embark on a chaotic quest for vengeance in the city of Dunwall while reviewing the Dishonored Roleplaying Game. A non-zero number of people get defenestrated in the process.

A quarantine keeps most of the citizenry inside their homes while exploited prison labor supports an elite family. A group of would-be thieves attempt to steal from a successful inventor, only to find out that his wife is the real inventor and she wants revenge. A protest is confronted by the authorities, but is allowed to spiral out of control after a bribe from another powerful party. Such is the world of Dishonored’s Empire of the Isles (as opposed to anything else it might be).

Dogan: “So all we’ve got to do is disassemble this whale, get the magic juice out of its bladder, and not explode in the process?”

Dishonored is a fun and faithful extension of the video game adventures through the Empire of the Isles. The game is at its best with an experienced GM, some familiarity to the source material, and a party willing to do some heavy roleplay. It’s also at times unambitious when it comes to novel material, although this can be left as an exercise for the GM. I’d recommend it to experienced gamers looking to advance beyond D&D 5e, but it can also work with mixed-experience groups. I would not recommend this if you’re looking to get behind the GM screen for the first time, if you’re not okay with a rather cynical world, or if you’re entirely new to Dishonored.

One caveat I will say immediately is that any reader is going to have to do a small amount of work parsing this book. While the core of the ideas all function, there are a number of typos, errors, and floating references in the PDF copy that I received. These things certainly should be fixed in later printings, as they caused me to lose my flow while reading, but the game works in spite of this. If this is going to be a deal breaker, then stay away until it’s fixed. If, on the other hand, you can work with incomplete information… well, you already know what I would recommend in that case, don’t you?

Elisabeth: “Every so often, I drink three or four blue elixirs in a row. Then I wake up and find I’ve invented something awesome.”

Dishonored uses the 2d20 system from Modiphius, which at its core plays more like Shadowrun than a system like D&D 5e. Checks are made by establishing a target number for a d20 roll, then rolling a number of d20 (usually 2) and checking for successes against a difficulty set by the rules or GM. The interesting thing about this system is that the stats don’t determine the number of dice in your pool but rather the target number to get a success for those dice. Each check is made using the sum of a stat (verb) and style (adverb) as the target, meaning that a check to Talk Quietly may have a different target number than a check to Talk Carefully or to Move Quietly. Unless the check is a contest between two characters, the GM announces the difficulty of the check before rolling, allowing players to use resources and situational advantages to mitigate that difficulty.

Of course, once the check is rolled, there’s very little that can change the result outside of some sort of occult magic, but that’s one of the strengths of the system. In a system such as FATE, where players can modify their dice after rolling, adjudicating a critical check can result in arguments over whether a tenuous aspect should give a bonus. Dishonored front loads this adjudication, making the roll that much more of a tense situation, since all the players know that once they put their plan into action, it either works or doesn’t, with very little room for modification.

Players do have plenty of ways to push for success, using both momentum, which is generated from extra successes on checks and is shared by the players, and Void, which represents the more occult things of the Dishonored world. In a pinch, the players can also give the GM Chaos points to improve their odds, which the GM can spend later to make the PC’s lives harder. When playing, we found that it was a bit hard to track momentum across the internet, but this should not be a problem at a physical tabletop. We also found that the GM shouldn’t be too transparent with Chaos, since it’s more fun for the players to not know exactly how big the metaphorical sword hanging over their heads is.

Lethal methods are fast and easy, but the cost is more than mere coin.

Combat, of course, is no small part of the Dishonored franchise and it’s played surprisingly, but refreshingly, loose. Combat uses an initiative of “what makes sense,” but includes initiative rules for people who want them. Likewise, distance and positioning isn’t a thing, instead relying on abstract ranges like “within reach” and “nearby.” The rules for actually hitting someone with a pointed stick are tight and fast. Weapons have static damage values that demolish health tracks, which may throw off veteran D&D players (combats were often resolved in less than 5 minutes). Additionally, melee attacks can be countered, meaning that a missed attack still progresses the fight. It’s a bit counter-intuitive that some weapons have different damage values in the hands of NPCs than they do in the PCs hands, especially since this information is in the GMs section, but it does make sense for PC survivability. Some weapons are strictly better than others as well; swords are usually less good than knives and clubs are strictly inferior to knuckle dusters. If the designers had given different properties to these weapons it would go a long way toward making them all viable options.

Stealth is another big part of Dishonored and I expected an elaborate system to deal with alertness and sneaking. In reality, the system is much more freeform. The infiltrated party has a stealth track, which the PCs inflict damage on if they fail to be stealthy, rather than be seen outright. This allows the less sneaky PCs to still participate, which can again throw off D&D veterans. When a party is attempting to be stealthy, their checks are harder, but the PCs can choose to succeed and inflict damage to the stealth track if they are a bit short of their target number. It creates a nice balance, as being stealthy is difficult, but that difficulty is relieved once the stealth track is filled, giving the PCs a chance to fight back after failure.

Magic is definitely in the game, but the core of it can be a bit troublesome. While Void can be spent to improve a situation, it doesn’t feel like magic when it happens. That isn’t to say there isn’t real magic in the game. Bone charms are small magic items that give a minor bonus and, occasionally, a drawback. They’re fun little magic trinkets and their mix-and-match nature means that you won’t run into the same one twice. True powers, however, are granted by the Outsider’s Mark, which feels like a direct transcription from the video games. The player and GM pick from a small list of powers, then the player collects runes to unlock them. While it’s flavorful, it’s odd to have a separate progression system for only one aspect of likely only one character, especially since runes are awarded arbitrarily by the GM. The powers, likewise, are direct transcriptions and I wish that the developers would have invented some new powers, especially ones that could only be done in a roleplaying game.

Powers are used very sparingly; there’s no pure “mage” archetype.

Progression is a freeform system, spending XP on individual bonuses and advances, rather than packages. Stats can be boosted, or that same XP can be spent on special abilities. These abilities feel strong and are often situationally powerful, but stats are more generally useful, creating interesting decisions. XP is gained from completing objectives in the game as well as from having specific bad things happen to you, like taking damage, encouraging players to take risks and balancing bad luck with faster advances. It’s a neat system and it averages an upgrade every two to three sessions, which is enough to keep players interested in the a la carte advancement. Oddly, the Outsider’s Mark is also an advancement, despite all the flavor suggesting it should be otherwise. While the book allows for a veto from the GM, it feels strange to have something this extraordinarily rare and fickle available for purchase at all.

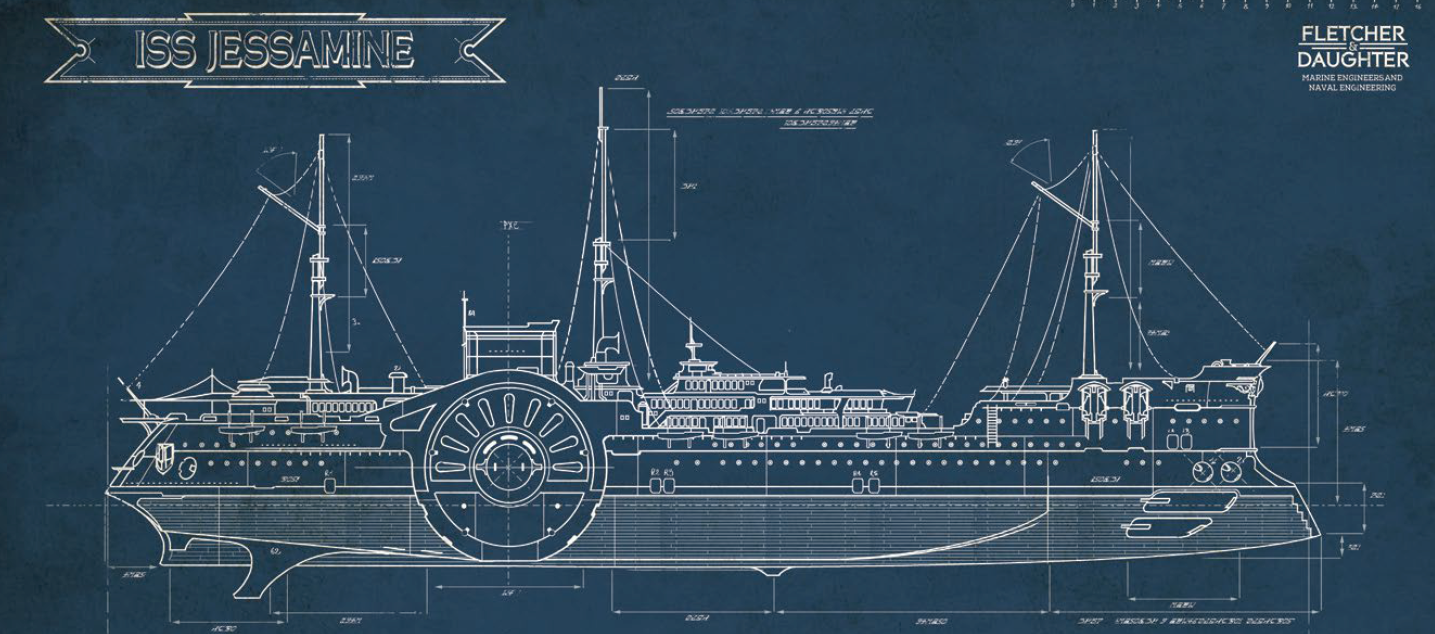

There’s a full description of both Dunwall and Karnaca, the cities from the games, each having a chapter on their own. These chapters have a LOT of material to work with and help to contextualize the information from the games in terms of the average PCs. I did wish that the other locations in the world had received a proportionate amount of attention, as I wanted to have hooks and jumping-off points for Morley, Tyvia, and especially Pandyssia (a place that’s somehow worse than Chult from Forgotten Realms). There’s enough of the two cities to explore that the relative emptiness of the world outside won’t be a big deal unless you play for a very long time or really, really want to go there.

The book also features an introductory adventure for starting characters. While we had a lot of fun and felt it to be a decent introduction to Dunwall, it’s a little strange for a number of reasons. The entire adventure takes place a while before the events of the first game, meaning that a lot of the interesting Tesla-punk things from the games don’t exist yet, while still referencing a lot of small things from the games. Most of the adventure feels like a Dishonored game, with sneaking, underground politics, and plenty of sidequesting. The book also divides the adventure into four sessions, which is slightly misleading, as we took ten sessions to finish the adventure. I will admit that we padded the length slightly, but not by much and it was a good excuse to use some of the adventure hooks suggested in the book. Each location or NPC in the book has one or two adventure hooks associated with it, meaning that you always have a way to work in your favorite elements, and they’re deeper than they look, often putting the players between two or three interested groups.

Lukas: “Nobody saw me use magic there, right?” Tony: “You were on the roof. Everyone saw you.”

So, should you pick up the game? If you want roleplay, politics, tense encounters, and trying to do right in a world with no good options, this game is going to be for you. If you want a game with a ton of options and flexibility to build the world how you want, you can have fun with this, but you’ll need to work with your players and GM. If you want a tactical exploration or combat game where you get to be the unquestioned hero, you might want to give this one a pass. I, for one, know that I’m going back for a sequel.

Special thanks to my players (Elisabeth, Lukas, Tony, and Dogan) and to Ken for dragging me down this particular rabbit hole.

Digital review copy provided by publisher.